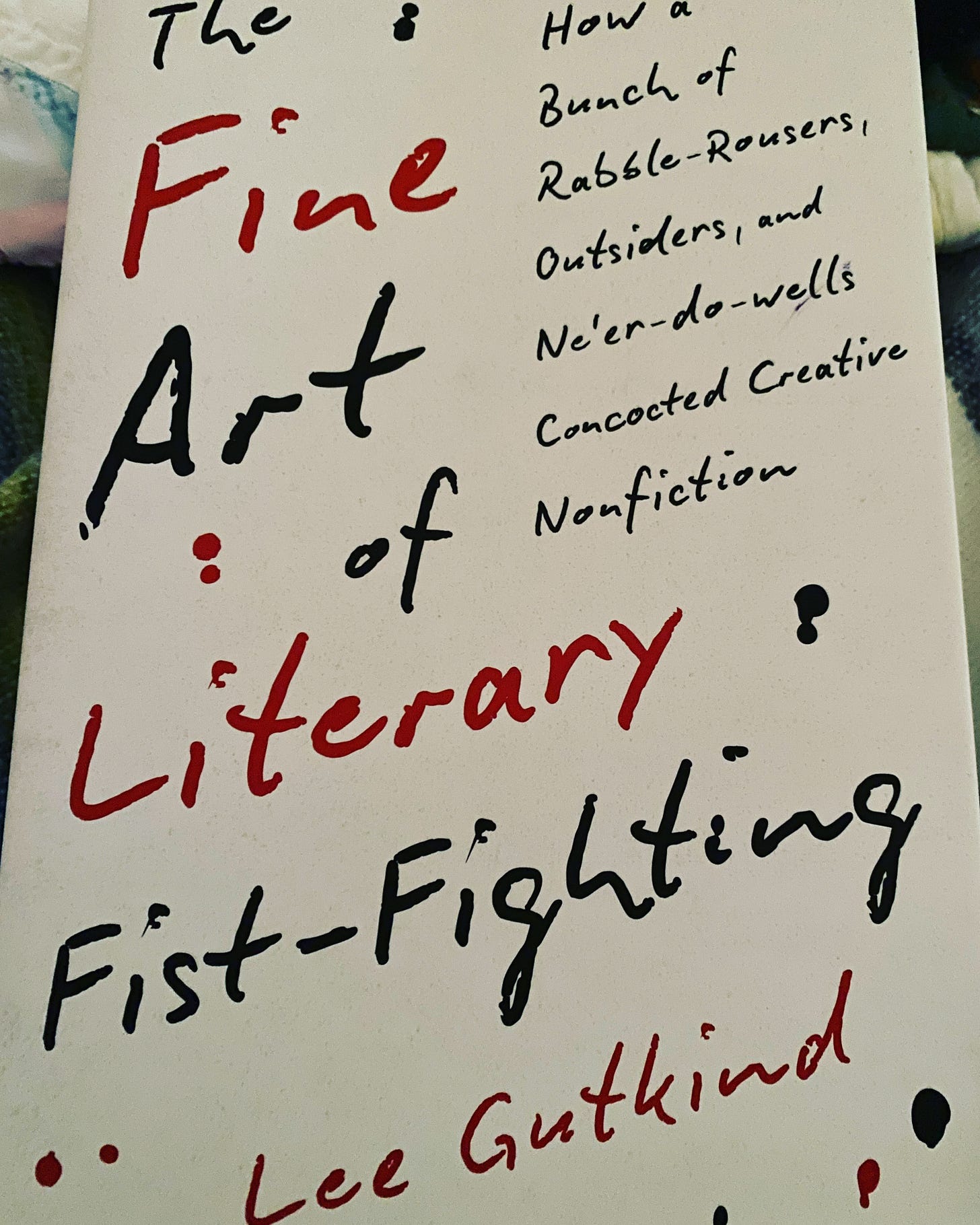

There is something about reading Lee Gutkind that always gives me pause, and reading his latest book, The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting: How a Bunch of Rabble-Rousers, Outsiders, and Ne’er-Do-Wells Concocted Creative Nonfiction only solidified this feeling. I’m glad I read it. Well, mostly glad. At times it felt tedious. At times it felt revelatory. At times it felt small.

Tedious: Gutkind really buys his own hype. And, I’m not saying he wasn’t important to establishing creative nonfiction as a genre, or the program at Pitt, or the journal-turned-magazine. But anyone who refers to the article that calls him the godfather of nonfiction feels, well, like that guy at the party who chats you up without letting you or anyone else get a word in edgewise, to the point where you find yourself really anxious to get away from him.

Also dropping things like the summer home in Jersey near Gay Talese. Tell me something exciting about talking with Talese. Like the one paragraph/sentence about the shirt boards:

“When he works, Talese, forgoing notebooks and index cards, takes notes on small pieces of shirt board recycled from his laundered shirts.”

This started, we find out, when Talese was writing for his high school newspaper, and he has notes from stories he wrote from that time on. I want more about that. Why the shirt boards? How? Not just that you met at such and such restaurant to talk. I felt like I wanted insight, or at least to be sitting in the restaurant, taking in more of what it was like.

To me, these passages are just name dropping. It happened more than in these examples. Each occurrence always put me off.

Revelatory: I was ready to be underwhelmed about Gutkind’s thoughts on Joan Didion, and, like most, he focused on the “pristine prose,” but one thing he said about voice, while maybe not revelatory, struck me as true. “Didion labored over each sentence, establishing an intimacy with her voice (emphasis mine) that would sustain her work and inspire readers and writers far longer than other new journalists.” There is an often under-talked about intimacy in Didion. I think that’s what highlights the coolness in her style.

Because Gutkind gives a fairly detailed and actually quite well-reasoned account of how the New Journalists—like Didion, Talese, Tom Wolfe, and others—paved the way to creative nonfiction (along with some others working in nonfiction forms, like essayists), he shows us an interesting trajectory. Although I’d argue that Didion’s work, which we should remember also includes fiction, moved away from the New Journalism and into creative nonfiction when she wrote about loss and grief. The Year of Magical Thinking uses her trademarks but in a new way—the cool sentences pull us close rather than keep us at arm’s length, the way, say, Slouching Towards Bethlehem does, where she feels both intimate and yet detached.

Speaking of distance between writer and reader, Gutkind does make a rather revelatory remark about what it was like to read James Baldwin that has stuck in my mind well past reading the sentence. On reading “Notes of a Native Son” he writes: “Baldwin was not just reporting with flair and style like Wolfe or Mailer; he was digging deep into an era of one young man’s life—so deep and so intimate that reading this essay was not really what I was doing; I was, rather, living the essay (emphasis mine), living Baldwin’s life with him.” He compares Baldwin to other writers, like Didion, Mailer, and Capote, who kept space between themselves and the story. “But in Baldwin’s prose, so intimate, so honest, that space disappeared.” His reaction to reading Baldwin is akin to my own, but I’d never had the right words to explain what had happened. Baldwin does bring you in to live his essays, which is why they are deeply felt reading experiences, and not simply read.

Gutkind also gives what I found to be a pretty good definition of nonfiction, which is difficult to get one’s arms around: “Creative nonfiction offers fact—information and ideas—presented in a cinematic way, often from a personal point of view that appeals to a general readership, people who would not necessarily be interested in the information with out the story to go with it.” Sure, it’s not perfect, but the genre, as Gutkind explains it, and as those of us who write in it know, is a big umbrella terms for a lot of different ways into true material. I sometimes appreciated the way he grappled with what creative nonfiction is and could be. He left some sense that it is still evolving, which probably is part of the reasons it’s so exciting to write.

Small: Gutkind mostly focuses on his experience, particularly while at Pitt, and around the creation of Creative Nonfiction. Granted, Pitt was the first MFA program to offer a nonfiction track. Significant? Sure. But he focuses rather narrowly on those writers in his orbit. His stories from the first issues of the journal in the early 1990s have a charming quality, but you’d get the idea that he and a few cronies were the only one’s doing this (except when he wants to show the reach at AWP, in which its a packed house…so which is it?).

And this made me think about my undergraduate experience with creative writing at Butler University, with Susan Neville, in the 1990s. She was an award winning short story writer when she also started publishing creative nonfiction, and her book Indiana Winter was part essay collection and part short story collection, tied together as a mediation on place. Susan was the first to expose me to the delights of creative nonfiction, and my capstone project was a chapbook of tiny essays on fishing—fishing with my family in Florida, and fishing with two old guys, one who owned a bait shop on a reservoir on the West side of Indianapolis. Susan really encouraged me to keep writing like this, and once, in class, gave me the single best piece of writing advice, which went something like this:

Writing is like throwing a boomerang. You see how far you can toss it out and still have it come back to you.

Just sit with it a moment.

And also, Susan invited writers to our reading series that included two Indiana-connected writers working in creative nonfiction: Scott Russell Sanders and Michael Martone. Sanders taught us how to be introspective while also appreciating the natural world. And Martone? His voice was so wry and funny, aspects I’ve been learning from ever since I first picked through The Flatness and Other Landscapes which came out not long before I started an MFA. Because I had first heard him read at Butler, I bought the book and read it first in one sitting. Upon re-reading, which I have done several times since I recognized in his writing voice something I wanted to cultivate in my own.

None of these three writers are mentioned in Gutkind’s book. And I think that it left me disappointed. Maybe not in that he missed three important writers to me, but I wondered who else had been overlooked. I got the sense he felt what he built at Pitt was some kind of epicenter and nothing else—or at least little else—was happening elsewhere. Maybe it felt that way—a big swath of his history happens before the internet, before cell phones, before social media. It could have felt like a creative nonfiction island at the confluence of rivers.

And still, it gnawed at me.

Odds and Ends

If you are not a subscriber of the New York Times, please enjoy this gift link to a Times Magazine article on Isabella Rossellini. In her 70s, she lives life more youthfully than most will ever live it—and certainly a good role model on aging for 51 year-old me. I have also found out her farm—Mama Farm—has a B&B, and this seems to me perhaps the perfect place to take a writing retreat. But I digress. Her thoughts on aging are well worth the read. “But then as you become older, you just are lucky to be alive and healthy. And then you start saying: Well, what do I want? Let me do what I want. I mean, short of hurting anybody.” She has made her life about curiosity and play.

Now that I finished the Gutkind book, I’ve been reading Several Short Sentences About Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg. Spare, funny, wry, and helpful.