I'd like YOU to comment...

Would you read on?

I know that this is a Substack called “I’d like to comment,” but now I’d like you to comment. I am polishing a memoir manuscript, The Night Is Yours Alone, and below I’ve posted the opening for you to read.

Draft pitch: The Night Is Yours Alone, is a grief memoir meets Gen X love letter, written for the introspective reader who picks up Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air, as well as the pop culture enthusiast who binge watches Stranger Things on Netflix.

At the end of this, I want to know one thing: would you read on? You can leave me any other feedback you’d like, for which I’m grateful. The poll at the end is simply “yes” or “no.” The comments are open for anything else you want to say, but I’m truly grateful just for the answer to that one question.

Also, parts of this work, in slightly different forms, were originally published in “Beautiful Things” by the literary journal River Teeth and in The Nassau Review. Deeply grateful to both publications.

Reunion Tour: Pictures of You

Thud of drums, The Edge’s guitar lick reverberating in our sternums, and the first flinty sound of Bono’s voice. We never expected “Sunday, Bloody Sunday.” A perfect choice. We turned to each other, big, surprised expressions like in a movie scene. My brother, Nate, fist-pumped the air, and we started moving, dancing in a sea of benevolent strangers. Nate, no longer a metastatic cancer patient. Years erased from my life with rheumatoid arthritis. And as the cool breeze wafted in off the riverfront, submerged in the music of our lost youth, we released: free, young, healthy, and above all, acutely alive.

The Night is Yours Alone

The camera lingers a moment after the final chords, and a small smile spreads across Sarah’s face. Not the wide grin of self-satisfaction, hers a shyer and perhaps truer smile—a lead singer’s smile, born from the shared purpose that comes from playing music together for the first time after months of pandemic separation. It’s mid-March 2021, and I am sitting alone in my home in First Ward, Morgantown, West Virginia, listening to local band Hello June cover R.E.M.’s “Everybody Hurts.”

Nate would appreciate this cover, I think. It would remind him of me.

Hello June’s YouTube video has a kind of late-80s-early-90s feel, colors like a developing Polaroid, a faint strobe-light effect. Around her neck, Sarah Rudy sports a navy bandana. She’s cut her hair super short, which somehow suits the rich alto of her voice. I can’t quite tell if the word “hurts” catches in her throat—if it’s the timbre or if the moment simply overwhelms—but seeing her with her band creates an ache in me for live music, embers from a long-gone youth. We’ve all been locked away from one another for so long that seeing musicians on screen playing together feels like watching a movie from a bygone era. Sarah sways as she sings and strums, as if comforting her guitar, and by extension, the rest of us who listen to this limited-circulation single.

This cover song confronts melancholy, hints at a hard-earned joy that often eludes me, not euphoric but a simple, quiet variety. Like a balm, the lyrics remind us that hurt is not, in fact, an emotion we experience alone, and I can’t help but wonder if sorrow and joy might attend one another.

Perhaps the lingering aftereffect of COVID is exactly that: everybody hurts—sometimes.

Everyone, except for Nate, of course. Nate’s gone. The night is his alone.

*

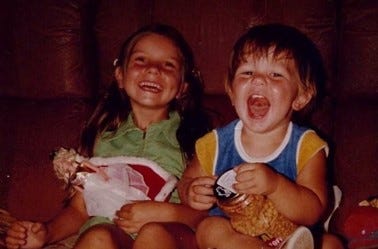

His texts would come out of nowhere, disrupting an otherwise ordinary day. Hey Ren, get a load of this! Then an old picture. Nate looks to be about three, which would make me somewhere between six and seven. His hair is sandy blonde, the way it was before it darkened into a deep brown like mine. Chubby-cheeked and smiling, his little hand thrusts a container of peanuts at the camera, the signature monocle of Mr. Peanut clearly visible on the label. We’re sitting on the old couch in our second home in Boca Raton, Florida, the dark leather brown except for the spots of wear, which by this point are plentiful, along with cracks where the cushions have begun to tear. It was the couch of our house in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and not long after this photo was taken, that couch would be replaced by a beige, cloth-upholstered L-shaped sofa, marking the transition of the ‘70s into the ‘80s.

In the photo, I’m smiling, too. My long hair is parted in the center of my head, pigtails sprouting from either side, the way I wore it nearly every day as a child. I clutch a Barbie doll by her legs, her blonde hair hanging in limp synthetic strands. If you zoom in, you might see the soft splay of freckles across my nose. My big round head looks precariously balanced atop my slight, girlish frame. Though I was petite, I was also curiously strong back then, like a twig that refused to snap. My blue eyes are barely visible because, when I smile, they turn into crescent moons, but Nate’s brown eyes appear big, bright and shining.

He texts again. I found it in a pile of junk.

I feel a twinge of relief that this photo has been spared the fate of so many of Nate’s other possessions, not relegated to a dusty box meant for Goodwill or shoved to the back corner of his already overstuffed garage or simply thrown away.

Look at us! I text back, trying to strike a balance between enthusiasm and breezy brevity. Despite our closeness when we were young, the adult versions of Renée and Nate are strained in a way that would never occur to the pair in the pictures, a problem compounded by my inability to articulate how and why this has happened. It just has. I know, too, that after this exchange, it may be months before I hear from him again.

The little girl in the photo is a simpler version of me, less complicated by life. Her roles were clear enough. She was a big sister, a girl who liked school, who learned to read early and quickly, and often got lost in words, whose first dreams involved tutus and tiaras. Her favorite Sesame Street character was Sporty Grover—not Grover, but very specifically, Sporty Grover who clads himself in all manner of athleticwear. Soon, she’ll move on to Stanley and Waldorf, the two geezers in the balcony of The Muppet Show who make witty jokes—at least witty to the six-to-seven-year-old set—at the expense of the rest of the show’s cast. They may represent the first iteration of my critic self, a voice that will, for better and worse, become one of my hallmarks in years to come, my way of being in the world.

Nate, by contrast, liked most of the Sesame Street and Muppet Show characters equally. His beloved toy was a stuffed koala bear he never named.

I save the photo to the digital album where I’ve been collecting pictures from my youth, including the random photographs Nate has been texting me. Among them, another snapshot of me, pre-Nate. A little girl in a Winne the Pooh nightgown, clutching a box that held a Fisher-Price cash register. My pudgy child hands strain at the corners of the box. My long brown hair lay partly pulled back, but strands fall over my face. A huge, pink stuffed Easter bunny sits on the couch behind me. My cheeks look round and pale, lips pursed in concentration. The carpet is rust colored, very ‘70s, and I can see just a sliver of the wicker swing chair I’d often sit in to read. Evidence that I’d lived several years before Nate was ever born, and though I don’t know it at the time, I’ll look back on this photo later, and think, it’s been several years since he’s been gone, and in that moment, both facts will seem so strange to me.

When this photo was taken, we’d moved to South Florida for my dad’s job, into a new open-concept home with a cathedral ceiling, what my parents described as “California Contemporary.” The kitchen and dining room opened, mostly, to the living space, and there was a half floor where my parents kept their bedroom. My room and Nate’s sat on the first floor, and I can picture younger me lying on her Laura Ashley floral bedspread, as though someone had puked flowers everywhere, surrounded by pictures of famous ballet dancers, listening to her pink cassette player and singing along with the soundtrack to my becoming. But what was that becoming? What lay ahead of me beyond that land of pink stucco and sailboats, a place I never belonged?

Those were questions that would remain unanswered until I was old enough to start going away for my ballet training. In the meantime, I’d find some access to the larger world far away from Boca, through the personal computer in our home. As the kids of an IBM-er, Nate and I grew up with a computer, early adopters compared to most Gen-X kids because my dad worked in the PC division. The machine was huge and performed very basic functions compared to today’s computers—so basic that it used a computer language called BASIC and came with an instruction manual that I would follow, learning rudimentary programming that would allow me to teach our computer to play tic-tac-toe against itself.

That computer sat on a long wooden table, set against the wall in the main living area of our Boca Raton home. It didn’t take us long to play through all the games that came with the early PC. There was an adventure game that required you to type in commands, and it was fun, up to a point, though less exciting to me than the choose-your-own-adventure books I collected. Nate and I would pull our chairs together and play, typing in commands like “Strike dragon with sword.” We’d tilt our heads toward one another, strategizing what move to make next.

The early PC also came with programs for professional development. One of those was called “Typing Tutor,” which did exactly that—it taught you to type, keeping track of your speed and accuracy. My brother and I “played” Typing Tutor as though it were a game. At eight, I had serious typing skills—90 words per minute without errors. Nate was even faster, his little fingers brushing the keys in a blur. We’d play until Mom grew tired of us sitting in front of the screen, shooing us out to ride bikes or cruise the neighborhood on our roller skates. We were always hauling out old blankets and towels to make forts in the shrubbery, hiding from the hot South Florida sunshine.

It’s weird now to think about how much computers influenced my young life. I had a computer for college, a weird portable machine that fit inside a suitcase. It was luggable but no fun to move because it was so heavy. I had an early laptop, too. I suppose I always had the means to write, even if I didn’t think of myself as a writer. Growing up, that technology encroached on everyday life but in a way that feels almost quaint now compared to the constant bombardment of screens and media today. Mom was right to make us go outside, and, when I sit to write now, I find myself starting with a pen on paper.

As a kid, Nate wanted to be a chef, an artist, an architect, and his games reflected those creative interests. He ended up becoming a marketing director, instead. Meanwhile, I followed my ballet dreams—a career ultimately cut short by rheumatoid arthritis, a trajectory I charted through a series of essays that ultimately became my first memoir, Fierce and Delicate. Nate would not live to see that memoir, but a copy of my most recent poetry manuscript would be found in his deathbed—poems I’d written about his illness, among other topics. I never heard what he thought of those poems, but at least he knew I’d been thinking about him.

Above my writing desk hangs snapshots of ballet-Renée. I wear pink tights with seams down the back, the kind I saw on pictures of dancers in the New York City Ballet. I also wear a white long-sleeved leotard with a pinch between the breasts, as if I’d really had breasts in those days. My hair is pulled back, blue eyes open wide toward the camera, my chin slightly cocked to the side, as though I weren’t quite paying attention to the fact I was being photographed. My legs open, floor to ceiling, 180 degrees, one foot planted on the Marley flooring, one toe pointed skyward.

In another photograph, I stand with a friend backstage, our hair perfectly pinned back, stage makeup exaggerating every feature. I can still feel the false eyelashes, like fragile, fringed wings. You can’t see my costume because I’m wearing an oversized sweatshirt with INTERLOCHEN blazed across it, collar cut out so that I can slip it on and off without messing up my hair or whichever sparkly headpiece the costume department chose for me. Even though the picture’s aged, my hair gleams almost glossy black, like polished onyx.

Unlike Nate, who followed practical career paths, I chased artistic dreams. Even after my dancing career was cut short, I turned to the equally impractical pursuit of writing. I read Joan Didion’s “On Keeping a Notebook” for the first time in a college English class and right then and there, I knew not only that I wanted to be a writer but that I wanted to be a writer like her. Didionesque. But I never could replicate what Didion does on the page.

Didion kept a tight rein on her sentences, only letting a whiff of herself brush along the prose, like the curl of smoke from the cigarette in her author photo, a pose. I found—maybe still find—that sense of coolness to be her writing’s hallmark, a detached all-knowing authority as she commented on culture, music, celebrities. In truth, she made culture. I wanted both her cool and her credibility (and maybe also her corvette). I checked out Slouching Towards Bethlehem from the college library and studied the rest of that book like a road map, but of all her essays, “On Keeping A Notebook” still resonated most because throughout my life I’d always been a notebook keeper. I’d read and re-read that essay, as if, though osmosis, each new reading might teach me to be more like her.

As a kid, I’d kept a locked diary, bought with my allowance money, from the local Burdine’s department store where a giant Hello Kitty loomed over the girls’ department. The diary had a strap that snapped into a tiny lock with an equally tiny key. I kept that key in my sock drawer, hiding it away, from whom, exactly, I don’t know. These, my young self felt, were private thoughts. Worth protecting. I don’t have that diary anymore, but I wish I did. A place for private thoughts seems healthy; not everything committed to paper needs to be made public. And yet here I am.

In middle school and high school I wrote in black and white college-ruled composition notebooks. I dutifully documented all my ballet corrections and my impressions of my classes, my teachers, other dancers. I recorded whole weeks and months of what I ate, jotted lyrics from songs I liked, and took note of new albums as they were released. I once wrote, “Listening to ‘Pictures of You’ from the new Disintegration album. The Cure always sounds like The Cure.” Next to it, I’d taped a fortune from a fortune cookie, something I often still do in my notebooks.

Lately, I’ve started collecting stickers from places I visit, using my notebook like an extended passport, the same way I used to keep ticket stubs tucked in the pages, a record of the many rock concerts and performances I’d attend—U2 tucked next to Prince tucked next to a multi-group set at the Cameo, an old punk venue, where I once heard this up-and-coming band, Red Hot Chili Peppers.

I also wrote down lines from books I was reading. In one notebook, I scrawled, “Her voice was full of money.” About Daisy, from The Great Gatsby, of course, a book I keep finding ways to love, maybe, especially, because it is the cautionary tale about wanting to recreate the past.

Didion made it seem like my notebook habit was more than okay. In fact, she made notebook keeping seem cool—at least, I thought so. In “On Keeping a Notebook,” she writes, “The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself.” Maybe I use this bit of Didion’s essay to justify my own compulsion to keep notebooks. I have accumulated a life full of them.

But where my writing is mostly a desperate attempt to distill meaning from the messy life I lead, Didion always seemed so unflappable and in control of what she was doing. Even after she tells you she’s a notebook keeper, she steps back from it, shifting into third-person to qualify that venture: “Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.” Didion has, basically, summed me up in this one sentence. With me, there has always been a fear of that which is just waiting to be lost. If I wanted to, I could view my life as a series of losses—my health and career to rheumatoid arthritis, my brother to cancer, my writing ambition to a rather ambivalent world—and so, I remain an anxious malcontent, as Didion puts it, never satisfied with what is, always both afraid and suspect of what might be, what might have been. Much of what gets scribbled in my notebook stays private. Some of it makes its way into my public writing. Either way, on the page I have, at least, some semblance of control.

Since her death, Didion’s ghost looms over me, larger than life. That’s okay, I’ve grown used to being haunted. If I spent my early years chasing ballet dreams, then I’ve spent at least a significant portion of my adult life chasing after Didion, and sometimes, I retreat into daydreams about the possible lives I might have led had I made different decisions, had I taken up the mantle and become an alternate version of myself. I imagine The New York Times describing my prose as “sharp, knowing vignettes,” and what it would be like to win a National Book Award, to read before a huge crowd. In my mind, I wear something stylish and colorful, maybe accessorize with my favorite Ray-Ban clubmaster glasses that make me feel cosmopolitan, if not sophisticated like Didion in her huge black shades. When I read, I take my time, my voice clear and calm, eliciting laughs in all the right places, those thoughtful sighs, too. I finish to thunderous applause. Later, I’m interviewed by Terry Gross. I imagine her probing and insightful questions, and my witty-yet-off-the-cuff answers. In this imaginary exchange, I am far more graceful and articulate than in my actual life. I say smart things about being kind to myself and connecting with others through grief, or how learning to cook during the pandemic helped me to better understand the craft of writing.

Me in actuality: I’m sitting in the glow of my computer, staring at the white rectangle MS Word tells me is a page. Cluttered desk, with lime sparkling water—sodium free! calorie free! sugar free!—and lozenges. Most of my pens no longer work, but they sit there in a tiny cup with a snowflake on it, beside three pairs of reading glasses, post-its, and little tablets. A book of poems I’ve been meaning to read gets hidden when I plop my notebook down on top of it, hoping to turn old scribbles into new writing. A photo of me twirling with two writing friends in a field, framed in aqua blue, sits beside a canister full of paperclips with a picture of a 1960s Barbie on it. I’m streaming a playlist of covers, Weezer’s take on Toto’s “Rosanna,” rocking out. It’s hot, and I wear a sundress, one that’s seen too many summers, but it has pink flamingos printed on it, and that reminds me of Florida and my youth, so I never get rid of it. I’ve had three cups of coffee and want another, but I resist the urge.

I am not the next coming of Joan Didion, nor will I ever be. My life lacks the glamour of my invented daydreams. Mostly, I sit in front of paper, wondering how to construct the next sentence—waiting, waiting, stalled out and stymied. I think, If I can figure out the next word, I might make it through this thing called life one sentence at a time.

Perhaps I had to chase after Didion to learn to be the writer that is me, full of her own quirks and idiosyncrasies. And maybe those writing dreams, the ones I never quite let go of, have less to do with Didion than I think. Maybe I had to lose Nate and survive a pandemic to let go of my inner and outer critics. Yet why so much loss for such modest gains? That doesn’t square either. I hide behind trying to say something smart—about culture, about death and mortality, drawing through lines where there are none—but I want to be more honest and earnest on the page. Authentic. To be both Sporty Grover and Waldorf and Stanley, and in the same moment, to let them go. To be both made and unmade. To search the past and imagine a future. But I don’t have the words to say how empty I feel since my brother died. And how, for many months after his death, I didn’t write anything at all. I’d sit down at my desk, and nothing would come out.

*

Whenever I feel out of sorts, I become a list-maker. It provides order and structure to my world, especially when it lacks those qualities. I don’t know if this is a Gen-X thing, a personal habit, a coping mechanism, or a writer’s tendency. All I know is that, over the past four years, trauma has piled atop trauma, and that list can feel insurmountable if I think about it too long—Nate went on hospice and died, I had no time or space to grieve. At work, I was asked to take on significant new responsibilities. And, as winter slumped into a wet, muddy spring, the world lurched into its pandemic place, and we all searched for new ways to cope.

During that time, I thought a lot about 1987. It was a year filled with possibility, young me discovering music, my life stretching out in an infinite playlist of my own making. R.E.M.’s Document. Prince’s Sign O’ The Times. U2’s The Joshua Tree. 10,000 Maniacs’ In My Tribe. The Cure’s Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me. The Smiths’ Strangeways, Here We Come. Depeche Mode’s Music for the Masses. Public Enemy’s Yo! Bum Rush The Show. The Replacements’ Pleased to Meet Me. Suzanne Vega’s Solitude Standing.

Maybe everyone remembers a certain year where music worked on them in an almost magical way. For me, 1987 was that year. Just old enough to start picking out music I would choose as mine, ‘87 imprinted itself on my listening habits in a way no other year had, before or since. Even a song like “Everybody Hurts” from 1993 takes me back to ‘87, when I first discovered the band that sang it.

There’s more: in 1987, Aretha Franklin became the first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Beastie Boys became the first band to be censored by American Bandstand. Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer” became a worldwide hit. U2 shot the video for “Where the Streets Have No Name” on an LA rooftop. Guns-N-Roses’ Appetite for Destruction, after a slow start, became the best-selling debut album to date. Fugazi played their first gig ever. George Michael’s Faith won the Grammy for Album of the Year. I rocked out at my first concert, The Joshua Tree, in early December, and soon after, I turned fifteen years old.

I picked my way through a heady mix of alternative music. Sonic Youth’s Sister. Echo & The Bunnymen’s eponymous album. The Jesus and Mary Chain’s Darklands. Siouxsie and the Banshees’ Through the Looking Glass. The Housemartins’ The People Who Grinned Themselves to Death. Red Hot Chili Peppers’ The Uplift Mofo Party Plan.

I looked to the future more wide-eyed than I cared to admit, balled up conflicted feelings and channeled them into a burgeoning interest in music, but I was afraid to see myself as someone really in-the-know. Girls like me didn’t become rock critics or a musicologists; I wasn’t, I wasn’t even the sort of kid who worked in a record store. It’s a form of imposter syndrome I’ve never quite shaken. But in ‘87, the music felt rich and thrilling enough that I didn’t care, throbbing through my headphones attached to a bright yellow Sony Sports Walkman that was practically an appendage. I lost myself in the songs, a current carried through my bloodstream by the steady drumbeats of the bands I queued up. I made mixtapes, listened to cassingles, on the go, slightly distracted.

Ramones, Halfway to Sanity. The Lemonheads, Hate Your Friends. Indigo Girls, Strange Fire. David Bowie’s Never Let Me Down.

Of them all, the three most prized albums in my collection were easily Prince’s Sign O’ The Times, R.E.M.’s Document, and U2’s The Joshua Tree. These would remain in my regular rotation long after 1987. Before my brother would die from metastatic colon cancer, he and I would go to the reunion tour for The Joshua Tree, where we would joke that The Edge looked exactly as he had back in ‘87. For whatever reason, it’s the year. A few things endure.

*

The internet offers so many opportunities to waste time, and among my favorite ways to trick myself out of writing is to research something online. Like Vans, the slip-on sneaker that was popular among Gen X skateboarders. They also happened to be Nate’s favorite shoe. While Nate showed only a passing interest in skateboarding, the Vans stuck with him, even after his skateboard wound up stashed away in a corner of our garage. He wore them up until he died.

Online, the Vans company website curates a timeline of their shoes, made to look like an old scrapbook. We Gen Xers love to make things on the internet look vintage-y. According to the timeline, in 1982, Vans Classic Slip-Ons gained international attention and appeal when Sean Penn wore them in the film Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Nate loved his checkerboard classic slip-ons, just like the ones Penn wore in the movie, though he bought his in the 90s. According to the timeline, 1991 was the year when Vans went public on NASDAQ. By 1995 they were sponsoring concerts.

For my part, I both loved and hated the 1990s, yet I keep listening to the music of that decade, perhaps because the ‘90s represent big, if common, turning points in my own life: college, first jobs. Not so common: rheumatoid arthritis. In 1993, among grungy hits like Nirvana’s “All Apologies,” a few alt. rock hits shouldered their way onto my playlists—Soul Asylum’s “Runaway Train” and Blind Melon’s “No Rain,” the latter featuring a video of a ten-year old in a bee costume that I still associate with the ‘90s, even now. R.E.M. seemed like the staid older brothers to these post-punk flannel boys. Is rueful the right word, the one I’m looking for? Not quite.

By late ‘92, when Automatic for the People came out, R.E.M. anchored my listening habits, shifting my teenage alterna-girl obsessions away from the jangly guitars and the mumbly post-punk lyrics that characterized the band’s earlier efforts—Life’s Rich Pageant and Document—toward this new sound that flirted with the mainstream. As an album, Automatic waxed nostalgic for an alternative scene that had since crested into the aggressive-if-murky sound of the new decade, and when the soul-diffused ballad “Everybody Hurts” somehow wedged its way onto the singles charts, it did so in spite of the grungy zeitgeist of the ‘90s and the sonic “meh-thos” collectively embraced by R.E.M.’s diehard Gen X fanbase. I counted myself among the collective shrug of my generation, anti-sanguine to a fault, yet, in songs like “Everybody Hurts” and its cousin, “Nightswimming,” I found the perfect soundtrack for all my moody early-adulthood tendencies. These songs became my angsty-self’s lullabies. Sort of nervous, kind of anxious, a bit eccentric, bordering-on-but-not-slipping-into true pop.

We let music imprint on us and we appropriate it into our self-story because somehow music penetrates our sense of reason with pure sonic emotion. I can see how R.E.M.’s music dovetailed neatly into the narrative I was constructing about myself as a young person. Alternative, quirky, artsy in that scribbles-in-a-notebook way, I grafted my young hopes onto R.E.M songs, wanting so much to be a particular kind of off-kilter, wanting the mystery of their obscure lyrics to apply to me. But to be young and female in the ‘90s also meant tamping down the desire for autonomy, and so I shoehorned all my ambitions of self-creation into a long, disaffected sigh and a gulp of Diet Coke.

One Christmas, before he dies, Nate will ask for a new pair of Vans. He’ll text me the size. Classic slip-ons. Checkerboard. On the day he dies, they sit in a box in his closet. Never worn.

*

On the bulletin board above my messy desk, hangs another photograph: me standing on Nate’s deck. It’s the Fourth of July, and I’m wearing a blue and white striped skirt with a sleeveless red tunic top, little red bows at the shoulders, a white straw hat with a blue and red ribbon, a sparkly rhinestone flower brooch pinned on the tunic, big black sunglasses hiding my eyes. I’m in a haphazard fourth position, which I instinctively stand in when I’m just hanging around, a holdover habit from my dancing days. My hands rest on my hips, but I’m smiling. Nate has just finished grilling our Fourth of July dinner, probably barbeque chicken or hamburgers, definitely corn on the cob wrapped in foil. This photo was taken before he was diagnosed. I know this because after he got sick, I took up the grilling duties, and as his cancer progressed, Nate would slowly stop cooking altogether.

One of my last memories before Nate’s quick decline was eating the delicious Brussels sprouts he’d fixed for his girlfriend’s annual Christmas gathering. No recipe. Completely improvised. I could never cook like that, and even in my recent COVID-inspired culinary attempts, with lovely fresh veggies from my local Community Supported Agriculture share, I lack the skill my brother had in the kitchen. For him, cooking was an outlet for his latent creativity.

Now, I try to cook more like he did. I try to understand the tastes of different foods, how to grill or sauté or roast to get the flavors out. Mostly, I make soup. The smell of vegetables simmering on the stovetop fills my house in autumn. Still, I’ll never be the cook my brother was. He had a gift for preparing food, and I wonder how it was that he never pursued becoming a chef, all the artistic ambitions he shelved while he was still alive. He had talent, maybe even ambition, but he never followed his childhood dreams. He studied advertising at Florida State University, joined the workforce right out of school. I’m not criticizing his choices, only trying to understand them because maybe they’ll help me to better understand him. Maybe, even help me understand who I was to him.

Few people will ever see the pencil sketch Nate drew of a penguin for his daughter. His hand steady, obeying the shape and line of the image in his head. Evidence, perhaps, that he never fully gave up on his artistic talent. He showed it to me during one of my visits, and I took a picture with my phone.

“I should have studied architecture,” he said, a simple lament in an unguarded moment not to repeat itself, yet it broke my heart.

When we were kids, he never seemed hemmed in the way he did as an adult. That’s true for all of us, of course, but for all my struggles to establish my own identity, I let myself follow my artistic dreams. I failed, often. I continue to fail, over and over. But I’ve always told myself that persistence is my great skill: I fail but I am not deterred.

And yet, since Nate’s death, I find myself staring at blank pages with a blank mind. Find myself staring at Nate’s penguin drawing for hours. A simple pencil-on-paper sketch, gray strokes on flat white, it’s the kind of artmaking I have no talent for. I keep wondering what, exactly, I’m looking for in it, as if it might hold some great secret about my brother I can’t quite reconcile. Perhaps, if I study it long enough, I might become privy to the way Nate saw the world. Perhaps, that might spur on my own creativity, the old desire to write, which has somehow abandoned me.

Old me, new me, future me—I find myself in a disjointed place, like my childhood and young adulthood have become scenes from a novel or a movie, with a character I can only vaguely relate to. Maybe that’s how grief works. We pull the threads of our past to see where it all started so that we might figure out how it is they’ve woven themselves into this tapestry of experience and change we call our present.

I struggle to look at pictures of Nate and me, can’t help crying when I do. It’s like pieces of my past have been cut out, existing only on tiny snippets of film that will one day disintegrate. It’s not so different from “Pictures of You,” the moody The Cure song, Robert Smith’s proto-emo voice conjuring up imagined photographs of an estranged lover. Smith invokes romantic love, but it’s the sense of longing that gets me. Yearning. I remember the closeness Nate and I shared as kids, like scenes plucked from a movie.

Yet, try as I might to avoid them, old photographs seem to fill my life. They’re inescapable. On my desk at work, in a tiny silver frame, sits a photo Nate’s daughter took with the retro-looking Instax camera I bought for her because it produced mini-Polaroid pictures like the kind we had in the 70s and 80s. Like the photos Nate would text to me. Only with rainbow edges instead of white, new and nostalgic at the same time. In the picture, my hair is still long and pulled up in a clip, and Nate and I wear bumming-around-the-house clothes. Kinda sloppy. He has his arm around me, and we are smiling.

At a family outing, my cousin Bill shows me an old picture: I’m in the pool, hair drooped in two drippy pigtails. I’m smiling, partially submerged in the water, wearing my favorite hot pink one-piece swimsuit. Toward the edge of the photo, Nate’s got water wings on. I can only wonder why he’s wearing them. He didn’t need them—from a young age he was a strong swimmer. He and I used to love to swim, all day, the pool: one of our favorite places. We had hoops with weights attached to them, and we’d make our own fun, submerging them to see who could swim through them the fastest. Nate was always one stroke ahead of me.

Even though he’s a ghost at the edge of the frame, the photograph reminds me of how close we used to be. I keep tracing my steps back, trying to figure out when that stopped being true, but I never quite pinpoint the moment. We drifted, and in the end, I don’t know that we ever fully regained that closeness, but there were flashes. Or maybe that’s what I want the photos to reveal. We attach meaning to photographs, just as we graft our story onto songs, and it’s all about the heavy little truths our hearts just don’t want to admit. Life can become laden with emotions it was never designed to support, burdened by a nostalgia that inevitably sinks to the bottom of the pool.

Sorting through Nate’s belongings, my parents will find a half-dozen notebooks Nate had been writing in. Only a few pages, mostly notes about the kids, groceries, work—each notebook abandoned shortly after it had been started. In my home in Morgantown, I have shelves and boxes full of notebooks, every page, every free space filled with my scrawling, half-cursive/half-print handwriting. My notebooks are the surest sign that I’m actually a hopeful person, not merely a malcontent, as Didion claims to be when writing about her notebooks. In one of them, I’ve written a note about an essay I hope to write, which simply says: Cure, “Pictures of You.” I am haunted by pictures.

Then I move on.

In one of my old teenage notebooks, I wrote, “I had to listen many times before these songs grew on me. Now the bass pulses like being in a sonic womb.” It’s not a bad way to describe Disintegration. Maybe my old self was onto something. She disintegrates and reconstitutes—if only, I can see now, I’d thought of the right words. But missing someone almost always ends up with never finding any words at all.

When Nate got sick, I bought him a notebook. A plain black moleskin, no lines.

“What am I supposed to do with this?” he said.

“Whatever you want,” I said.

He smiled. I thought he might draw in it. “No,” he said. “I think I want to write.”

After he died, my parents found it among his belongings, the pages completely blank.

*

To believe in a remake requires you to grab onto trembling hope. It marks a place where past and present converge. The rhythm: Nate died. Da-dum. A beat not of my choosing, the repetition in all my writing nowadays, a desperate grasp for who I will become in his absence. Nate died. The hook and the refrain.

Then the whole world turned in a way none of us could imagine, and “before” and “after” took on new meanings.

During the pandemic, I thought about Nate a lot, wished I could talk with him. My self-talk, which had often been directed toward telling me, “Hold on, hold on, it’s going to be okay” in a more abstract sense, felt sharp, pulled into focus. Sometimes I’d cue up songs we’d listened to together, but it didn’t really help. My brother would never know the pandemic.

As we emerge now from this lonely, sad time, maybe a song like “Everybody Hurts,” a sonic postcard from an earlier decade, serves as a survivor’s anthem. When we talk about disease and illness, we tend toward metaphors of battle—enemies and victories and losses—but our current moment isn’t about victory. It’s about how we persist, one day after another, until one day a shy, relieved smile spreads across a singer’s face, and suddenly, it’s as though the only way I have ever heard this song performed is by Hello June, the insistently intoned “hold on” both lyric and directive, because we have not, in fact, had too much of this life, and though tired, we’re aware of how much we simply want to live as once we had.

Nate will never hear Hello June’s cover of “Everybody Hurts.” I’ll never get the chance to send it to him. It’s a particular sadness that grips me when I think he only had 42 years on this earth, especially as I careen headlong into my fifties. There are so many dead. I keep thinking about this, keep writing it down, as if I might forget it, but of course I won’t.

I don’t know if it’s the mix of female voices in the Hello June cover, or the timing, or my early connection to R.E.M in general, but the song hits that sweet spot, and on my first listen, I find myself crying, stray slow tears that slide down my cheeks. A bittersweet release of all I have pent up.

Hang on, Sarah sings. What else can we do?

I won’t remember what else is going on this particular day, when Sarah sends me her message with the preview link to her video, but as I listen to the song, it becomes apparent that the night is Hello June’s, only I am allowed entrée. It’s said that listening is the most powerful and underused skill available to us, vital and real, a gateway to compassion, and so I re-queue the song, playing it over and over, and I hold my memories up to the night sky, like photographs, the twinkling stars and equally shining space junk, our imperfect world that we keep mucking up and destroying. Our cloudy future doesn’t look anything like the future of that girl who discovered music back in 1987. But it’s also not unlike the future she imagined. My cheeks are tear streaked as I take in my Hello June gift. I, too, am a remake. And so, the night is also mine.

But I am not alone. And though I’m not yet sure of my new voice. I pick up my pen, and for the first time in months, I write, recalling a past self who discovered a powerful force in the music that spoke to her. Turns out, that’s the part that never went away.

***

Thank you for reading. I truly appreciate it.

Music has this unique ability to transport us back to specific moments in our lives, both happy and sad, and it's clear that your beautiful tribute makes it clear how music plays a significant role in your journey. t's a testament to the enduring impact of the 90s culture on those of us who grew up during that time, and how it continues to influence us even as adults!!

Ok, so I would definitely read on. When I’m looking to read the start of a memoir, I want, most of all, some sense of what I’m getting into as well as a sense that this/these are people I’m interested in following for another 200ish pages. And all of that is true here. The writing itself is also really good. I’m impressed at how much ground it covers without feeling haphazard or chaotic. I think that’s because each cut from one thing to the next is handled in a really clear way. And so everything—the band that frames this opening, the musings on Joan Didion, the 80’s pop culture insights, the IBM details, and all the photographs that lead us in this journey—it all feels fresh. That’s the other thing: in a book dealing with grief, I tend to appreciate a fresh angle, instead of just watching people mourn, and I get the sense from this opening that, while the book may have parts that are legitimately sad, it’s going to be about more than that. I hope it gets published soon so I can read more!